Haemochromatosis

WHAT IS HAEMOCHROMATOSIS?

WHAT IS HAEMOCHROMATOSIS?

Hereditary haemochromatosis (inherited iron overload disorder) is the most common genetic disorder in Australia. About 1 in 200 people of northern European origin have the genetic risk for haemochromatosis. People with the condition absorb too much iron from their diet. The excess iron is stored in the body and over time this leads to iron overload.

We all know that not enough iron causes health problems but few realise that for some, too much iron is also a problem. If undetected and untreated, the excess iron can cause organ or tissue damage and can potentially result in premature death.

Haemochromatosis tends to be under-diagnosed, partly because its symptoms are similar to those caused by a range of other illnesses.

Both sexes are at risk from haemochromatosis. Women tend to develop the condition later in life because of blood loss during child bearing years. However some women will develop symptoms at an early age.

The good news is that if haemochromatosis is detected before damage occurs, it can be easily treated and is no barrier to a happy and successful life.

Absorption of iron

Iron is a vital trace element that we get from our daily diet. The body is finely tuned to take in only as much iron as it needs. Red blood cells contain the protein haemoglobin, which carries oxygen around the body. Iron is needed for the production of haemoglobin.

The human body has no method of getting rid of excess iron. It controls iron levels by absorbing just the right amount of iron from our food. Any excess is stored in organs and joints in the body.

Haemochromatosis can affect the body’s ability to regulate iron absorption and can lead to too much iron being taken up and stored. It is this excess iron which can cause harm.

Effects of iron overload

The body typically stores around one gram or less of iron. However, a person with haemochromatosis absorbs a great deal more iron from their food than is necessary. Iron stores of five grams or more can build up inside the body. Organs such as the liver, heart and pancreas can be affected and ultimately damaged. Without treatment, haemochromatosis can cause premature death.

For people with haemochromatosis the excess iron stored in the organs and joints increases gradually over many years. If untreated, the liver can become enlarged and damaged, leading to serious diseases such as cirrhosis or liver cancer. It can also cause other health problems including heart disease, diabetes, endocrine and sexual dysfunction and arthritis.

Other forms of haemochromatosis

There are other forms of haemochromatosis which are rare but important – Juvenile haemochromatosis and non-HFE haemochromatosis. This website focuses solely on hereditary haemochromatosis.

Symptoms

In the early stages of iron overload caused by haemochromatosis, symptoms may be completely absent or very nonspecific.

These may include:

- general fatigue and weakness

- weight loss

- abdominal pain

- joint aches

These symptoms, if present, take time to develop. No two people are alike and symptoms will vary from person to person.

In cases of higher levels of iron overload, symptoms vary depending on the organs affected. Higher levels of iron impact the liver, joints, pancreas skin and sex organs and the symptoms may be different from person to person.

Higher levels of iron can cause cirrhosis of the liver and liver cancer. People with liver problems may develop an enlarged liver, jaundice, easy bruising and pain in the liver.

The heart can be affected in rare cases and symptoms will include palpitations due to damage of the heart muscle, breathlessness with physical activity and swollen ankles.

If the pancreas is affected this may lead to type 2 Diabetes Mellitus with symptoms including thirst and increased need to urinate, skin infections that don’t heal well, blurry vision, dizziness and weight gain or loss.

Rarely, people will present with a grey or bronze discolouration of the skin.

Women may experience irregular periods or early menopause and loss of libido while men may experience impotence and shrinking testicles.

DIAGNOSIS

Hereditary haemochromatosis is diagnosed by simple blood tests. Your doctor may order the tests if your symptoms indicate haemochromatosis is possible or if you become aware a close relative has been diagnosed with the condition.

Parents, brothers, sisters and children of people diagnosed with haemochromatosis should be tested. However it is not necessary to test children before their late teens unless symptoms develop early.

Iron Studies

These blood tests look for two indicators that signal someone may have haemochromatosis.

They measure Transferrin Saturation and Serum Ferritin.

They are usually a fasting blood test.

Reference ranges for Iron Studies:

Male

Serum ferritin:

20-300 μg/L

Transferrin Saturation:

10-50%

Female

Serum ferritin:

10-200 μg/L

Transferrin Saturation:

10-45%

Reference ranges may vary slightly with different pathology service providers.

If the results of these tests are above the reference range, they are repeated.

If the second test again exceeds the range, a genetic blood test is necessary to confirm haemochromatosis.

Genetic Test

The gene associated with haemochromatosis is known as HFE.

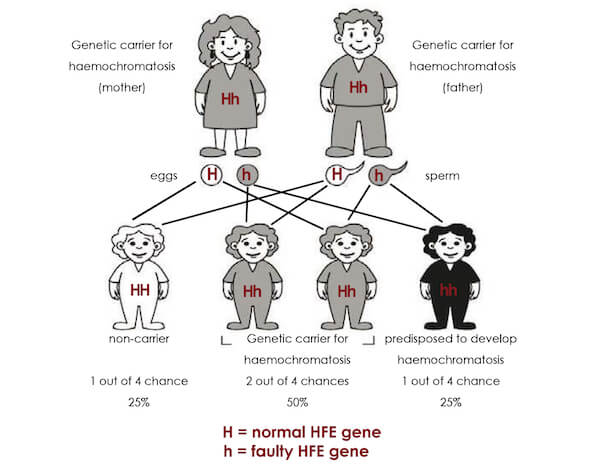

Haemochromatosis occurs when the genetic test shows they are homozygous, that is they have two faulty copies of the HFE gene.

A person who has only one faulty copy is heterozygous and will not experience any symptoms but is known as a “carrier” because they may pass the condition to a child.

There is strong medical evidence of a potential for significant organ damage when iron stores cause serum ferritin levels above 1,000 µg/L. However some people seem to experience symptoms with levels between 300 and 1,000 µg/L. Higher levels are more likely to be associated with more severe symptoms.

GENETICS

GENETICS

Genes contain the information the body needs to develop from the first cells to the grown adult body. Genes come in pairs that are formed with one from the father and one from the mother.

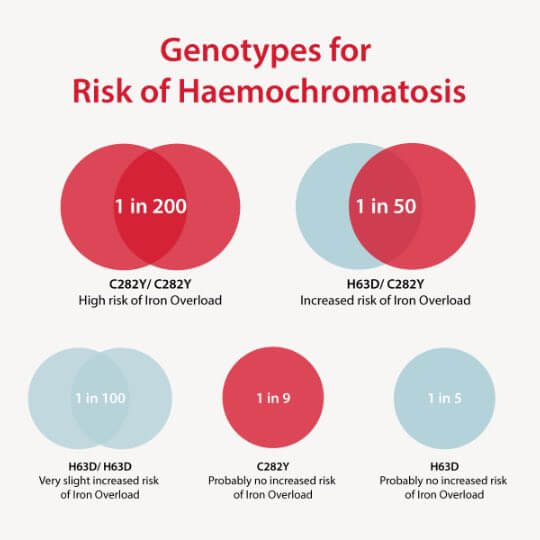

While several different mutations of the HFE gene have been discovered, there are two main mutations or faults that cause hereditary haemochromatosis. These are referred to as C282Y and H63D. The C282Y mutation is associated with most cases of hereditary haemochromatosis. The H63D mutation seems to have less impact as do the other much rarer types.

Haemochromatosis is a recessive gene disorder. That means for the condition to be passed on, both mother and father must have one copy of the abnormal HFE gene. About one in seven people have one abnormal HFE gene. They are referred to as a ‘carrier’ because they carry a gene which may cause their children to inherit the disorder. Carriers won’t develop the condition themselves.

Risk of iron overload

Homozygous = two copies of the same mutation

Compound heterozygous = one of one mutation and one copy of another mutation

Heterozygous = one copy of the mutation and one normal copy (carrier)

For a more detailed explanation of the possible genetic test results, see our Information Sheet 1: Genetic test results and haemochromatosis Mutations: What is your genotype?

How does this affect my family?

It is important that immediate family members know if they are at risk of developing iron overload. Parents, children, brothers and sisters should have the genetic test..

It can be difficult to talk about these things and sometimes family members are reluctant to listen. You can download a letter suitable to email or post to your relatives here. It explains what they need to know in simple terms and they can take it to their own GP to discuss testing.

Download the letter here.

Non-HFE haemochromatosis

1 in 700 people with haemochromatosis have no mutation in the HFE gene. This is known as Non-HFE haemochromatosis and is due to mutations in other genes.

TREATMENT

How is haemochromatosis treated?

Up to 500mL of blood is removed at regular intervals until the iron levels in the blood return to within the normal range.

This can take up to 18 months with weekly or sometimes twice weekly venesections, depending on the original iron levels of the patient.

Once normal levels of iron are re-established, venesections are used less frequently (three or four times a year) to maintain those levels throughout the patient’s lifetime.

At what level should treatment begin?

At what level should treatment begin?

At any level above normal – the iron levels should be normalised as quickly as possible. Permanent damage, such as cirrhosis, occurs with iron overload and is irreversible. Your doctor will set up a treatment schedule for you.

Where can I have my venesections done?

My Iron Manager app

Our My Iron manager app for smartphones and tablets has a searchable map with locations we know of where venesections are performed. The map includes Lifeblood donor centres and mobile locations.

If you discover an error on the map or find another place where venesections are performed please let us know at feedback@ha.org.au.

Australian Red Cross Lifeblood

The Australian Red Cross Lifeblood has a therapeutic venesection program for individuals who have iron overload as a result of hereditary haemochromatosis.

Many people with haemochromatosis can attend Lifeblood for venesection and they are able to use your donation to help save lives. If you are not eligible to donate blood which can be used to treat patients, Lifeblood may still be able to offer a therapeutic venesection service unless there are medical issues that would present a donor safety issue.

To be accepted as a therapeutic donor, you will need an online referral from your doctor using the High Ferritin App.

Many of our members are pleased to be able to contribute to saving lives. We even have our own Lifeblood Teams that you can join (just search for ‘Haemochromatosis Australia’ and pick the group for your state). Lifeblood Teams are a life-saving social responsibility program where workplaces, community groups, and universities around Australia unite to save lives through blood donation. Your friends and family may come along to support you and donate at the same time. They can join our Lifeblood Teams too.

Other Options for Venesections

Other Options for Venesections

For various reasons, not everyone can donate through Australian Red Cross Lifeblood or do not have access to a nearby donor centre.

Other options for venesection include:

- Many hospitals have regular venesection clinics

- Some GPs will perform venesections in their surgery

- Some pathology companies will perform venesections. It is usually best to ring and enquire first as not all collection centres provide this service

If you are having trouble locating somewhere to have venesections, ring our InfoLine on 1300 019 028. We may be able to suggest somewhere.

PREPARING TO GIVE BLOOD

Making the Appointment

You may not always be able to choose your time, but if possible, pick a time that suits you. Choose a time when you won’t be rushed or stressed. Some people prefer mornings, others afternoons.

On the Day Before

On the Day Before

Make sure you’re feeling well.

On the Day

Drink plenty of fluids the day before, especially in warm weather. Have at least three glasses of water in the three hours before. Your blood volume goes down a little when you give blood.

Eat something salty in the 12 hours before. You lose about three grams of salt with each donation, so this is your chance to eat something salty, like chips guilt-free. Have a good meal in the three hours before.

On the Couch

Do these muscle exercises before the needle goes in or comes out, before getting up, if you feel dizzy, hot or nauseous

- Cross your legs

- Squeeze your inner thigh and abdominal muscles

- Stretch your ankle

- Hold for five seconds then relax five seconds

- Repeat five times then switch legs

After giving blood

- Take it easy

- Have a snack – something salty is good

- Have a drink – water, cordial or energy drinks

Do

- Keep the bandage on for at least 2 hours

- Continue to drink fluids – at least three glasses of water or juice

Don’t

- Stand for long periods (sorry, no window shopping on the way home)

- Avoid standing in long queues or crowded public transport

- Get overheated. Stay away from hot showers, sitting or standing in direct sun, and hot drinks

- Do strenuous exercise like riding, jogging or going to the gym

- Smoke for at least 2 hours

- Drink alcohol for at least six hours

After a venesection, the body uses Vitamin B12, folate, iron and protein to make new blood. People undergoing frequent venesections (giving blood) during the initial de-ironing phase of treatment may find Vitamin B12 and folate supplements helpful to boost the ability of the body to make new blood cells and cope with the process. You should seek advice from a pharmacist or your GP.

RESOURCES

We offer a huge range of resources for health professionals and their patients